New Study Calls for Early Action as Lungs Begin to Decline Sooner Than Earlier Thought

A new study that tracked lung growth from childhood to old age has called into question long-held views about how our lungs grow and age. This study demonstrates that lung function begins to decline shortly after peaking in early adulthood, rather than in middle age as previously thought, and it was conducted by an international team led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal).

This shift in knowledge is based on a large dataset of over 30,000 people aged 4 to 82 in Europe and Australia. The researchers employed an "accelerated cohort design" method, which combines data from many long-term studies to map lung changes during a person's lifetime. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine published the findings.

"For a long time, we believed that lung function rises until the mid-20s, stays steady for about 15 years, and then declines after 40," said lead researcher Judith Garcia-Aymerich. "However, our data does not support this. There is no stable phase. Instead, the drop begins immediately following the apex.

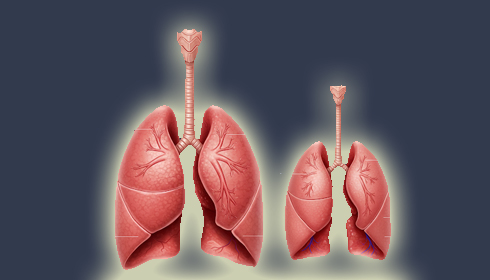

Scientists use a test known as spirometry to learn about how our lungs function over time. This test determines the amount of air you can exhale after taking a deep inhale. Spirometry produces two significant results: FEV1 and FVC. FEV1 indicates how quickly your lungs can push air out in the first second, whereas FVC assesses the total volume of air you can exhale. According to a recent study, lung function peaks at age 20 in women and around 23 in men. Surprisingly, there is no plateau—after reaching this high, lung power gradually declines.

Using spirometry, a test that records how forcefully and thoroughly one can breathe out—researchers assessed two important lung health indicators: FEV1 and FVC. FEV1 shows us how quickly air can be ejected in the first second, while FVC informs us how much air comes out overall. The study found that lung strength did not remain steady for long. Women achieve their maximal lung capacity by the age of 20, whereas men peak slightly later at 23. Following that, lung function gradually declines, with no periods of rest or halt.

The researchers discovered that both asthma and smoking impair lung function, but through different processes and at various periods of life. Persistent asthma impairs lung development from an early age, resulting in diminished lung function throughout infancy and a lower peak capacity in early adulthood. This early deficit may raise vulnerability to respiratory problems later in life. In contrast, smoking—particularly after the age of 35—has been shown to accelerate the natural deterioration in lung function over time. Individuals with heavy and chronic smoking histories experienced a substantially larger impact. These findings demonstrate how asthma causes early vulnerability, whereas smoking exacerbates the damage in later years.

This means that people with asthma have weaker lungs to begin with, while smokers exacerbate their existing conditions— a hazardous combination if both are present.

These findings could change the way we screen and treat lung health. The notion that our lungs are stable until middle age provided doctors a false sense of security. We now understand that by the time symptoms manifest, the decline may be well advanced.

"This tells us that we need to act much earlier than we thought," said Dr Rosa Faner, one of the study's senior authors. "We should start monitoring lung function in children and young adults, especially those with asthma or at risk of smoking."

Early use of spirometry, the simple breathing test employed in this study, may aid clinicians in detecting poor lung development or early injury. Once detected, lifestyle adjustments or medical interventions can help avoid long-term diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which causes breathing problems and is frequently diagnosed too late.

The World Health Organisation ranks respiratory disorders as the third biggest cause of death worldwide. Most public health efforts have focused on older folks, but this study implies that we should start much earlier—even in childhood.

Policies that discourage smoking, minimise air pollution, and provide asthma care in schools and clinics may help protect lung health in the long run.

"This is a wake-up call," explained Garcia-Aymerich. "Healthy lungs in adults are developed during childhood and adolescence. If we lose the opportunity for early prevention, we will pay the consequences later."